By Vivianne Ihekweazu & Atinuke Akande-Alegbe (Lead Writers)

“Is Nigeria no longer the GIANT OF AFRICA? Why are we not producing the Covid-19 vaccine yet or we’re waiting for free doses of vaccine from foreign aids?” This sentiment was shared on Twitter in December 2020 and has been echoed in multiple forums since the onset of the race to produce a COVID-19 vaccine.

Many lives have been irreparably affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and global economies devastated in its wake, resulting in over 2.2 million deaths in just over 12 months. The emergence, rapid spread and impact of the virus led to the outbreak being declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) within a month of the first reported case in Wuhan, China in January 2020. The level of devastation caused by the virus could never have been imagined, but one year down the line, the world is coming to terms with its full impact.

At the start of the pandemic, very little was known about the transmissibility and virulence of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, nor was much known about the preventive measures needed to prevent infection. Scientists advised on preventive and control measures based on similar viruses and from previous epidemics and pandemics. As the virus rapidly swept across the world, it became clear that many of the assumptions that drove the initial response were insufficient to prevent transmission and an increasing death count. Our knowledge had to be quickly updated in order to develop strategies to defeat this new virus.

China shared the full genetic sequence of the new virus on February 7, 2020, about a month after the initial announcement of the outbreak. Following this initial report, collaboration among scientists saw the sharing of data and virus sequences in real time, enabling scientists to track the pattern of transmission of the virus. This was done by reporting the sequencing to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). This platform was established for the sharing of influenza virus sequences.

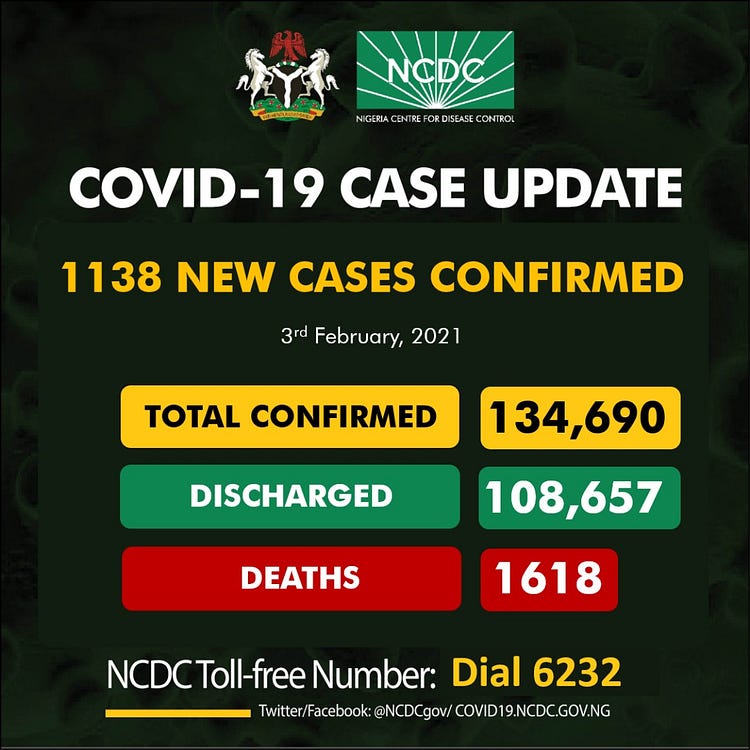

Following the detection of the virus in Nigeria, the spotlight quickly shifted to Nigeria and our domestic capacity to respond effectively to the pandemic caused by this new virus. This led to a flurry of activities and commentary never seen previously as science was thrown into the spotlight and became the subject of simultaneous discussions across different sections of our society.

A new virus and science in Nigeria

There was great concern at the onset of the outbreak that once the virus reached the African continent, it would prove very difficult to control, given our existing weak health infrastructure and high burden of other infectious diseases. A further concern was that the limitations in the development of scientific and technological capacity may constrain the ability of African countries to mount a robust, science driven response to limit the spread of the virus. However, in less than a month after the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Nigeria, the first complete sequence of the virus in Africa was carried out by a consortium that included the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID), the Nigeria Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) and the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). This was only made possible by the scientific capacity that had been previously developed in institutions like ACEGID, using their networks, and established molecular capacity that had been built up over years of investing in the scientists and facilities, which offered an enabling environment for research to thrive.

Human capacity for science research

Biomedical research actually dates back to the establishment of the West Africa Yellow Fever Commission in Yaba, Lagos in the 1920s. This led to the establishment of other research institutions for Yellow Fever in West Africa. According to Professor Tanimola Akande, a Professor of Public Health at the University of Ilorin, “Nigeria used to produce Yellow Fever vaccines and instead of progressing to develop the technology and other resources for more production, the country has since stopped”. The government has set up several committees, initiatives and task forces to revive vaccine production. In 2017, The Federal Ministry of Health signed an Memorandum with May and Baker that aimed to start vaccine manufacturing by 2019. This arrangement appeared to have stalled, until N10 billion was recently announced by the Federal Government of Nigeria to support vaccine production in Nigeria.

As we progress through this pandemic, it has become increasingly obvious that there has been insufficient investment in science education, our scientific institutions and in the training of research scientists over many years. The initial growth of the early science institutions seemed to face an even more difficult time during the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the early 1990s, leading to significant cuts in government health and science expenditure.

The Nigerian Government has long had the ambition to improve the capacity for science and technology in Nigeria. The setting up of science and technology schools, special science primary and secondary schools and Federal and State Technology Colleges in Nigeria was in a bid to strengthen the foundation of science and technology education in the country, with the expectation that it would help develop the expertise and capacity for science research. However, the funding to these colleges was never sufficient and students in many of these technology colleges had to study in poorly equipped laboratories and training facilities, made worse by poorly motivated and poorly remunerated science teachers who had access to limited training opportunities.

“From the basics, primary and secondary education teachers, particularly in the public schools, no longer have well qualified teachers and science laboratories to stimulate knowledge of the young ones in science and to get them know adequately the basics in science”, explains Professor Akande.

So, despite these efforts, the development of science and technology has been poor, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the weakness in our domestic scientific foundation and highlighted the importance of science and technology in the national development of global economies, especially low-and-middle-income countries like Nigeria.

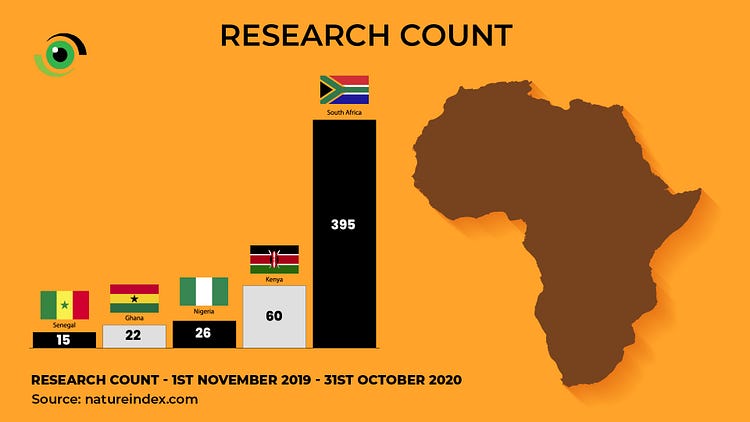

At the tertiary institution level, we are also struggling. The quantity and quality of research papers coming out of higher education institutions in Nigeria has been much lower than other African countries. Iruka Okeke, Professor of Pharmaceutical Microbiology at the University of Ibadan, says that, “Nigeria has a comparatively large number of scholars engaged locally in scientific pursuits at universities and research institutes, but tenders fewer competitive research proposals to international funders.”

The Nature Index, which is updated monthly, tracks high-quality research articles by institution and country and shows that countries like Kenya and South Africa are investing more in scientific training and research, and have done better in attracting grants from international institutions. To understand the Research count, one count is assigned to an institution or country if one or more authors of the research article are from that institution or country.

Making the investment case for science research

The opportunity for collaborative research partnerships between scientists and institutions in the Global North and sub-Saharan Africa has shown great inequity, even when the research focus is primarily in a sub-Saharan African country. In a recent Twitter post, Dr Ngozi Erondu, Senior Research Fellow at Chatham House Centre for Global Health Security, lamented that a $30 million global project to fight malaria, awarded to seven institutions, did not include a single one from a sub-Saharan African country where the research would be taking place. Many intuitions, who themselves appear to be champions against inequity and advocates for justice, do not seem to see anything wrong with the status quo.

The consequence of this situation is that Nigerian postgraduate students often move to countries which provide them with better access to research funding and a more conducive environment to develop their research capacity. Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, Associate Professor and Principal Investigator of the COVID-19 vaccine studies at Yale School of Medicine, stated that, “Mentorship, high quality training opportunities, research funding and collaboration opportunities are key things that have been more available to me in the US”. Once they move, many of them stay back, contributing to the development of these countries.

There is a strong investment case for science research in Nigeria. Growth in many of the countries that Nigerians look up to, has been driven by knowledge-based economies which require a concerted investment in science education, especially tertiary institutions. “The global move to introduce discovery-based laboratory classes in science courses has barely taken off in Nigeria”, says Professor Okeke. More resources and steady investment is needed for science to thrive. But discovery-based science and implementation science is “not valued by society or government” according to Professor Ibrahim Abubakar, Director of the Institute for Global Health at the University College London, UK. Science education requires long term investments, providing sufficient time for findings to come to fruition. Funding for science cannot be solely dependent on government funding, as foundations and large corporates need to come to the table to invest in Nigeria’s higher education institutions.

Now, with a pandemic devastating our economy, we are yet again vulnerable and dependent on research and technology for diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines from countries that have built up their own domestic capacity in science research. Nigeria has remained only an end-user of these products. We must begin to put the work in to build our domestic capacity in science research. There are a number of steps we must take:

1. Setting a foundation for Nigeria’s science capacity

In order to prepare for a future where we are not only recipients of science, but full participants, Nigeria needs to have a much stronger educational foundation in science to build the necessary research capacity, right from primary schools. Explaining the need for a rethink of our science education and the pedagogy of teaching, Dr Alero Ann Roberts, Senior Lecturer and Consultant to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital said, “It is heartbreaking to see generations of Nigerian youth who have never had the simple joys of discovering magnetism by playing with iron filings or looking at Spirogyra under a light microscope”. She went on to say that, “students need to learn through explanation and reflective discussion, with opportunities to critically appraise problems and design solutions”. This sentiment was echoed by Professor Okeke when she said that “scientific discovery of the very basic kind is little appreciated by Nigerians”.

For Dr. Ogbuagu, “Universities should be at the forefront of research and innovation,” however, they have faced “systemic challenges” that are common to other sectors including mismanagement of funds and challenges attracting and retaining the best qualified staff.

There is no doubt that Nigeria has the potential, as we saw in the case of the five students from Onitsha, who won a place in the global finals of the Technovation Challenge in Silicon Valley, California, USA.

Other issues that have contributed to the poor foundation of science research in Nigeria include a “lack of coherent leadership”, according to Professor Abubakar, while for Christian Happi, Professor of Molecular Biology and Genomics and Director, African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID), it is “the entrenchment of mediocrity in academic institutions in Nigeria”.

2. Developing scientific institutions in Nigeria

According to Professor Okeke, who is also a Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Sciences and the African Academy of Sciences, “Academic budgetary cuts to science negatively impact the quality of teaching we can offer,” and this has an impact on research and development in universities. In addition, our current university structures have their inherent inflexibilities and are not open to attracting and appointing external academia. They are “structured to encourage locally trained scientists to remain, rather than to recruit talent from abroad,” Professor Okeke added. Science requires exchange to thrive. Where almost all the faculty in a department grow out of the same group, very little exchange happens, and science stagnates.

Professor Akande noted that, “Progress in developing scientific institutions is slower in Nigeria due to the lack of prioritisation of research”. This presents an opportunity for the public and private sectors to collaborate and fund research programmes in Nigerian institutions.

For COVID-19, the private sector played an incredible role by stepping up and taking responsibility in partnering with state governments in the response, providing facilities, equipment, funding, health worker support, and infrastructure. These can also be replicated to develop our scientific institutions. South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) can serve as a model for public-private research institutions. CSIR, with about 3,000 technical and scientific researchers, is a public institution that benefits from funding from corporate South Africa. Its founders recognised that a collaborative approach to research between the public and private sectors leads to better outcomes and innovations. Research which is led by local scientists and scientific institutions is vital in overcoming the many health challenges that Nigeria faces. But, in addition, there is a need to “collaborate with more foreign and regional institutions to strengthen research capacity,” Ogbuagu suggested.

Professor Happi bemoaned the inadequate interest and investment by the private sector in research and supporting research institutions. The government needs to ensure the private sector has an enabling environment to invest in science research. The Serium Institute of India serves as a model of an indigenous biotechnology and pharmaceutical company that systematically built its capacity over many years to become the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer.

3. Creating an enabling environment for Nigerian scientists

Despite the many challenges of the Nigeria context, we have to acknowledge the advances that scientists in Nigeria have made. They continue to make giant strides in many areas of endeavor, despite the limited resources made available to them. Noting this, Professor Okeke said, “These successes are reflecting in a number of areas connected to the pandemic including local patient management in treatment facilities, testing and genomic surveillance.” For Dr. Roberts, “there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that Nigerians are clever, innovative, hard-working, happy, easily content, and patriotic.”

However, unlike their counterparts in other parts of the world, who reach the top of their field of work, Nigerian scientists do not have the enabling environment to support them. Dr. Roberts shared an example of the recent one-year long strike by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU). “We cannot forget that the crux of the dispute was fulfillment of basic government promises to educate and develop its own national human resources, remuneration for work already done, funds to equip and maintain learning infrastructure.”

In 2017, in partnership with NOIPolls, Nigeria Health Watch conducted a survey looking at the emigration of medical doctors. Some of the findings revealed that about eight out of every 10 medical doctors in Nigeria were currently seeking work opportunities abroad, attributable to factors such as low work satisfaction and poor salaries. The brain drain is not limited to doctors, as several other healthcare practitioners and scientists continue to leave the country en masse.

To create an environment that inspires scientists, Prof. Akande said that the government and the society needs to better recognise and reward researchers who come up with great findings, as is done in other countries. Their research outputs can also serve as evidence to inform policies for national development that will benefit the populace. “We need a cultural shift towards valuing research,” Prof. Abubakar said.

4. Meeting the demand of science-based industries

For Prof. Happi, our government needs to identify local scientists with adequate knowledge and experience and entrust them with resources to develop vaccines. Emphasising this, he said, “There is no country in the world that has ever developed a vaccine or other novel pharmaceuticals without strong government incentive or investment.” In addition, Prof. Abubakar recommended “programmes to train academics and researchers in grant writing skills, management and delivery of programmes within the context of structured opportunities in order for them to flourish in a competitive and funded environment”.

In order to meet up with the demands of Nigerians to build up science-based industries, Professor Okeke shared the example of how Thailand established a vaccine institute to produce flu vaccines to guard the country against any potential shortages. Even though the vaccines were produced at commercially uncompetitive prices, the government still supported the initiative, setting up vaccine plants which would be repurposed for other vaccines. “That kind of value proposition and investment could kick-start vaccine production, drug formulation and even discovery in Nigeria,” Prof. Okeke stated.

5. The role of science in the COVID-19 response

COVID-19 has made evident the pressing need for countries such as Nigeria to prioritise science. For science-based policies to succeed in Nigeria, we need public trust in science. To gain this trust, we must popularise science and share its benefits in people’s lives. In fighting pandemics such as COVID-19, where public health measures are needed to prevent the spread of the disease, trust in science is essential to effect behavioural change.

Translation of science evidence to policy, according to Dr. Ogbuagu, is one area that the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) has done well. For him, “We have experts who know how to interpret available evidence, ask the right and insightful questions and formulate policy that aligns with available evidence. If anything, I think the issue here, is how to communicate and disseminate policy to the public in a way that can be understood and that is culturally appropriate. We compete with misinformation and rumours which create an unfavorable environment for science and science policy.”

What role can publishing play in policy making for science? Prof. Okeke said, “If we disseminate our findings through the high-quality peer reviewed literature, they are more likely to be picked up by science media, which is a good way for them to slide into the political discourse”. Dr. Abubakar also believes that more leadership is needed to convince political leaders on the value of science by professional bodies — the academy of sciences, health professional and academic societies.

Charting a way forward

1. Investment in the country’s science education by increasing the quantity and improving the quality of science teachers and lecturers in the country, ensuring they are able to work in a conducive environment with well-equipped facilities and laboratories. Also, ensuring they are adequately remunerated with access to continuous professional development opportunities.

2. Greater collaboration in scientific research, bringing together people with diverse expertise across various research institutes, within Nigeria and internationally. This would help speed up the acquisition of expertise in Nigerian institutions, as new knowledge and technology would be introduced which would spur innovation.

3. Strengthening the capacity of local researchers, as well as our research institutions in Nigeria to attract more grants. This will also require institutions in Nigeria to improve their grant writing skills but will also require grant making organisations in the Global North to be more intentional in funding `north-south’ collaborations between institutions, rather than perpetuating historical inequities.

4. Future proofing our health workforce and providing scientists and researchers with the resources and access to training opportunities to ensure they can compete with their counterparts globally.

5. Development of better communication capabilities of scientists so they can craft convincing narratives and messages for diverse audiences, such as private sector investors, government and various stakeholders. They would have to be able to articulate the investment case for science research, and why it is a win-win for the country, and a means to drive sustainable economic growth.

As the Chinese proverb says “The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.”

Nigeria is a great nation also GIANT OF AFRICA. But as giant of African we have to do many things that shows really we are the giant, especially during this time of world challenge of Covid 19. Our health institutions still not well equipt. So Nigeria Health Watch should meet the FG to do something better.

Thank you for your comment Mr Yahaya, the development of vaccines and other pharmaceutical products is very complex. However, there needs to be an intentional effort by the government to build the enabling ecosystem to make this possible. This starts from strengthening STEM in school to activating a generation of future scientists who seem themselves as the future leaders in scientific research and discovery,